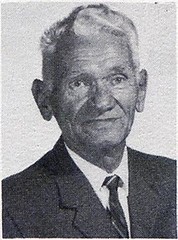

Late in life, Herman Schmieding decided to learn Spanish, and then he decided to teach Spanish to his sixth-grade class. I think our class, which he taught in 1963-1964, was the first or second class that learned Spanish from him. I don't know whether he continued teaching Spanish to the following two classes before he retired.

He told our class that he could have taught us German instead, but that he thought that Spanish would be more useful for us in the lives we probably would lead. That might be true, but I think that the primary reason was that he himself was more interested in the Spanish at that time in his own life.

He did not teach us very much Spanish. We didn't have textbooks, and learning Spanish was not part of the school's curriculum. He didn't teach us Spanish every day, and when he did teach it, he didn't spend any more than about 15 minutes on his lesson.

He taught us the meanings, spellings and pronunciations of a few common words and phrases. I still remember the following:

Buenas dias,Señor Schmieding ¿Cómo está Usted?

Good day, Mr. Schmieding, how are you?Estoy bien, gracias. Y usted?

I am well, thank you. And you?¿Qué día es hoy?

What day is today?Hoy es lunes ... martes ... miércoles ... jueves ... viernes ... sábado ... domingo.

Today is Monday ... Tuesday ... Wednesday ... Thursday ... Friday ... Saturday ... Sunday.Por favor, cuente hasta diez.

Please count to ten.Uno, dos, tres, cuatro, cinco, seis, siete, ocho, nueve, diez.

One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten.Muchas gracias.

Thanks a lot.

He made only an experimental attempt to teach us some Spanish grammar. One day he passed out to each student a mimeographed sheet that introduced grammatical gender. Every noun is masculine or feminine (even if it seemed neuter to us English-speakers) and the possessive pronoun had to match that gender. So, for example, the word libro (book) is masculine and the word pluma (pen) is feminine, so we were supposed to say un libro and el libro but una pluma and la pluma.

After only one or two such grammar lessons, however, he abandoned his efforts to teach us grammar. He recognized that he could not teach us grammar in occasional 15-minute lessons. He continued only to teach us various word groups, such as niño - niña (boy - girl), and desayuno, almuerzo y cena (breakfast, lunch and dinner). We never progressed significantly beyond that primitive level of instruction. In the end, we learned only a smattering of Spanish.

Even at that time when I was only about eleven years old, however, I was impressed that Mr. Schmieding himself had decided to learn Spanish when he was in his sixties and nearing his retirement. His motives for his decision and for his expenditure of time and effort intrigued me. As I recall, he mentioned that he had attended summer-school classes at the University of Nebraska to study Spanish, and he mentioned that he intended to travel (or already had traveled) on vacation to Mexico to practice his conversation skills.

A year or two after I finished sixth grade, I had to go to Mr. Schmieding's house on some non-school day to drop something off or pick something up. I can't remember what this task was about; perhaps it had something to do with my job delivering newspapers. This was the only time I ever went to his house, and I was there only for one minute at the door. I came to his door and knocked, and he came to the door, and I gave him whatever the item was or he gave me whatever the item was, and then I left.

What suprised me in this incident and what I still do remember is that he came to the door wearing a brightly-colored, floral-design, short-sleeved tropical shirt. I normally would call it a Hawaiian shirt, but in this context I suppose it actually must have been a Mexican shirt. Also, his hair was not groomed as tightly as usual; he was not wearing any hair pomade, so his hair was a little tousled. Any of you who had Mr. Schmieding as a sixth-grade teacher can imagine my surprise. We students saw him only as a very formal man. It seems that his Spanish-language hobby stimulated a different part of his personality than his students normally saw.

After I graduated from the eighth grade, I began to teach myself Russian as a hobby. Looking back now, I think my new hobby was encouraged by Mr. Schmieding's example, although I was not conscious of that association at the time. He had not given me any useful foundation for language study or inspired me with any passion for language study, but he had showed me that a person can teach himself a foreign language on his own. That was the seed that he planted in my mind that eventually became fruitful in my own life.

The idea of learning Russian occurred to me the first time when I was browsing through books in the children's room in the Concordia College library, when I was in about seventh grade. I happened to find a book about the history of Soviet espionage in the United States. This book claimed that in order to train its spies to speak English well, the Soviet Government had set up a small, artificial-American town where everyone spoke English and followed an American way of life. The spy students would live in this artificial-town for many months and thus perfect their English-speaking and other spy skills. Of course, this information captured my imagination, and I intensely envied those Russian spies who enjoyed such an unusual and fascinating experience. I imagined how wonderful my own life would become if I ever were selected to learn Russian in an artificial-Russian town that the US Government likewise might maintain in some remote location to train its own spies.

I soon adjusted this fantasy from a spy scenario to a Lutheran-missionary scenario. I figured that if I could learn to speak Russian like a native, then I should sneak into the Soviet Union and encourage and guide the underground church there and convert individual Russians to Christianity.

My fantasies about learning Russian for secret purposes remained idle and inert until my family was visited by my Aunt Marion and Uncle Hal in Seward in the early summer of 1966. Aunt Marion was not my biological aunt, but she had been informally adopted into my mother's family and grew up as a quasi-sister of my mother. After I was born, Aunt Marion became my godmother, a responsibility that she took seriously. She tried to develop a close relationship with me, and I tried to reciprocated her effort.

Aunt Marion's husband Hal (my Uncle Hal) had served in the US Navy for a few years and had received Russian-language training during his service. It so happened that during their visit to us in Seward in the early summer of 1966, the movie The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming was opening in the movie theaters, and of course Uncle Hal wanted to see it, because (he had read) it had a Navy theme and had a lot of Russian dialogue. The movie was not showing yet in the Seward movie theater, but it had opened in movie theaters in Lincoln. Being the dutiful wife and godmother, Aunt Marion wanted to make Uncle Hal and me happy but doubted that we would want to travel all the way to Lincoln to see a movie, but after some discussion Hal and I agreed that we indeed were willing to travel so far. I wanted to spend time with Aunt Marion and Uncle Hal, and I also was intrigued by the opportunity to see a movie where there would be a lot of Russians talking.

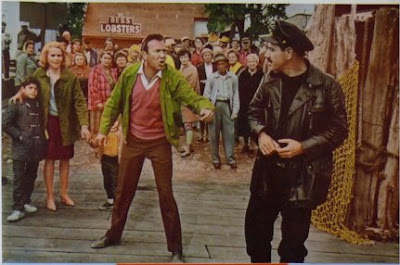

So, we traveled to Lincoln and watched the movie, and we all liked it very much. The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming is a delightful movie. The movie was nominated for four Academy Awards (Best Picture, Best Actor (Alan Arkin), Best Film Editing and Best Screenplay Adapted From Another Medium). I have seen it five or six times in my life, and I always enjoyed it.

The movie depicts a comic situation that develops after a Russian submarine accidentally runs aground on a remote beach in Massachusetts. Nine members of the crew sneak ashore to find and borrow a motorboat to use secretly to push or tug the submarine off of the beach. Despite their efforts to avoid detection, the Russians soon are noticed by some inhabitants of a nearby small town, who deduce mistakenly that the Russians are part of a major Soviet invasion of the United States. Eventually, however, the Russians explain their accidental grounding, and the Americans recognize that these Soviet sailors simply want to get away without causing problems. The Americans help the Soviet sailors get away, which is a happy ending.

The movie does include a lot of Russian dialogue, because the Russian characters do speak Russian among themselves. Since the role are played by American actors, the Russian is not spoken with native accents, but the words are Russian. After the movie, Uncle Hal told me that he understood most of the Russian dialogue, which impressed me strongly.

I decided that I would teach myself Russian, so the next time that I traveled to Lincoln with my family, I bought a Berlitz teach-yourself-Russian book and began to teach myself. I never had any audio help -- records, tape recordings, a real Russian speaker -- to help me with my pronunciation. I just sounded out the words as best I could from the book's written descriptions of pronunciation.

I kept at this hobby on-and-off for the next three years. I would work at it for a few months and then drop it for a few months. My family moved to Eugene, Oregon, after my sophomore year in high school. At my new high school I had one study hour every day, and I usually spent that time studying my Russian.

Between my junior and senior year in high school, I attended a first-year Russian class in summer school at the University of Oregon. Then during my senior year I commuted to the Univesity every day to attend the second-year Russian class. After I graduated from high school, I enrolled in the University as a full-time student and continued to study Russian, although I considered myself to be a pre-med major. During my sophomore year at the University, I decided not to become a doctor, and I became a Slavic Languages major.

In order to graduate with a degree in Slavic Languages, I had to study one other Slavic language and either German or French, so I studied also Czech and German.

In the summer of 1971, I attended a two-month Russian-language program based at the University of Leningrad and then traveled around in Czechoslovakia by myself for one month. In the following summer of 1972 I attended a two-month Czech-language program at the University of Brno in Czechoslovakia and then traveled around in Poland for a month.

During the following years I taught first-year Russian, first-year Czech and first-year Polish at the University of Oregon as a graduate student and eventually earned a Master of Art's degree in Slavic Languages.

In 1978 I joined the US Air Force and then served for 14 years in Intelligence. During 12 of those years I served in the organization that interviewed immigrants and defectors for the US Intelligence Community.

I left the US Air Force in 1992 and then worked the next decade translating documents for the US Department of Justice's Office of Special Investigations, which investigated and prosecuted former Nazi collaborators who had immigrated from East Europe to the USA after World War Two. During that decade I translated hundreds of documents from German, Russian, Polish, Ukrainian and Belorussian.

Perhaps if Mr. Schmieding had not made his brief effort to teach us Spanish in the sixth-grade, then I would not have bought that teach-yourself-Russian book a couple years later. My life then would not have followed the course that it has followed. He planted one small seed in my mind, and that seed grew and gave me the main direction in my life.

Steve Sylwester commented:

Mr. Schmieding taught my class — his last class — Spanish, too. I was a poor (read: uninspired) student, but I did learn the greetings. Years later, I was bold enough to greet Mr. Schmieding in Spanish one day, and then the inevitable happened: he responded to me in Spanish, and I had no idea what he was saying. We both laughed about it, and that was the last time I ever saw him.

No comments:

Post a Comment