When my family lived on Faculty Lane, I could walk to the Concordia College library in a couple of minutes. I spent a lot of time there.

I don't remember how I was able to check out books. I don't think I had a library card. As I remember, the place where the books were checked out had a set of cards with the names of faculty kids who used the library, and I simply stated my name, and the clerk verified that there was a card for my name and then checked out the books to me. I used the library often enough that usually the clerk recognized me and so did not have to look for the card.

The library had a special room with books for children -- for elementary-school pupils. While I lived on Faculty Lane, I selected most of my books from this room.

One of the books I found in the children's room made a huge impact on my life. This book was a history of Soviet espionage in the United States. The book included a chapter about a Soviet spy ring that was discovered because of some information that was provided by a paperboy. The story is told in this website:

On June 22, 1953, a paperboy for the Brooklyn Eagle, knocked on the door of one of his customers in an apartment building on Foster Avenue in Brooklyn. The paperboy was going through the month-end ritual of collecting from his customers. The lady customer only had a dollar bill and the paperboy did not have enough coins to make change so he asked the neighbors next door if they could help. The neighbors pooled their coins and produced enough change for a dollar, and the bill was paid.

As the paperboy was leaving the apartment building, and jingling the change in his hand, he could not help but notice that one nickel weighed less than the other nickels.

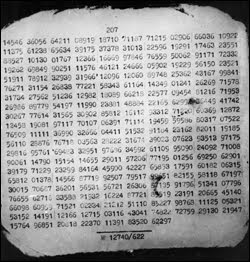

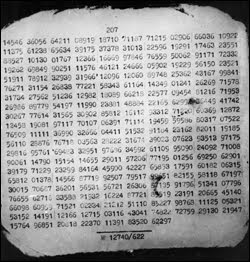

As he examined it, it fell to the ground and opened up after hitting the cement sidewalk. Inside was a miniature photograph showing numbers arranged in columns.

Two days later a New York City detective casually remarked to an FBI friend about the hollow nickel a newsboy had discovered. The detective had received the information from another police officer whose daughter was acquainted with the paperboy. The New York City Police picked up the nickel with its contents and turned it over to the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

FBI agents in the New York City office examined the hollow nickel. The interior of the coin appeared to be what agents described as a microphotograph portraying 10 columns of typewritten numbers. There were five digits in each number and 21 numbers in most columns. Suspecting a coded espionage message, the agents shipped it to the FBI Laboratory for further analysis.

Following its arrival in Washington, the coin received careful scrutiny by a team of FBI scientists. Hollow coins, occasionally used in magic acts and only occasionally seen by the FBI, were seldom if at all, seen by ordinary citizens. The coin was indeed unique, even for the FBI. It was a Jefferson nickel with a tiny hole drilled in the letter R of the word "TRUST." Investigators concluded that the tiny hole had been made to accept a device to open the coin. The other side of the coin had been made from another nickel minted during World War II and composed of a copper-silver alloy.

As efforts began to decode the message on the microphotograph, FBI agents in New York launched an investigation. The neighbors who had given change to the newsboy for a dollar bill knew nothing of the coin and confirmed that they had never seen such a thing. Proprietors of novelty stores and other businesses in the area were contacted and photographs of the hollow coin were shown to them, but this failed to produce anything positive. A detailed canvassing of the neighborhood did not yield any useful information. The meaning of the microphotograph seemed destined to remain a mystery.

From 1953 to 1957, attempts to solve the mystery of the hollow nickel by interviewing former intelligence agents who had defected to the free world from communist-bloc nations shed no light on the case. FBI investigators checked out hollow subway tokens, other hollow or trick coins but none appeared to suggest a tie to the one discovered in Brooklyn. The search for the person for whom the coded message in the nickel was intended was nowhere to be found.

Seemingly unrelated events can occasionally bring solutions to insolvable mysteries. The key to the paperboy's hollow nickel proved to be a lieutenant colonel in the Soviet State Security Service (KGB). The 36-year-old officer telephoned the United States Embassy in Paris and subsequently in an interview stated that he had been operating as a spy in the United States and needed help. The spy, Reino Hayhanen, explained that he had just been ordered to return to Moscow and felt defection was better than returning for an uncertain future.

Mr. Hayhanen had been born on May 14, 1920 near Leningrad to two Russian peasants. Despite this modest background, Hayhanen became an honor student and in 1939 earned the equivalent of a certificate to teach high school. In September of 1939, he was appointed to a primary school in the village of Lipitz. His high level of proficiency in the Finnish language, however, attracted the NKVD or secret police. Two months after beginning his job as an elementary school teacher, the NKVD drafted him to go to the combat zone and translate captured documents and interview prisoners during the Finnish-Soviet war.

When the war ended Hayhanen was ordered to review the loyalty and reliability of Soviet workers in Finland and to develop sources of information in Finland. His real job was to identify anti-Soviet elements in the intelligentsia. By 1943, he had gained considerable respect for his knowledge of Finland and Finnish matters and was accepted into membership into the Soviet Communist Party. At the end of the war Hayhanen received promotion to the rank of senior operative and worked in the village of Padani, identifying dissidents. The KGB called Hayhanen to Moscow in the summer of 1948 and gave him a new assignment. He would be required to learn English, sever all connections with his family and receive special training in photographing documents as well as in the encoding and decoding of messages. While his training continued, he worked as a mechanic in Valga, Estonia, and in 1949 entered Finland as Eugene Nicolai Maki, an American-born laborer.

[The article continues on the linked website.]

This story captured my imagination. Another chapter in the book claimed that the Soviet Union had a secret town where everyone spoke English and all the signs were in English, and this town was where the Soviet spies learned to speak English like native Americans.

This book gave me the idea that I should learn to speak Russian perfectly and then sneak into Russia and secretly convert a lot of Russians to Christianity.

The library's children section did not have any books about how to learn Russian, so I went into the adult section and found three books about the Russian language. None of these books was useful, because they were not introductory books. One of them was the second-volume of a old textbook set, and the other two were collections of reading texts for intermediate students who had learned some of the language from other books. I checked out all three books and took them home and looked through them, but they did not enable me to teach myself Russian. (I described how I eventually learned Russian in this article.)

The library's children section also enabled me to learn about sex. I found a few books about puberty, and I read them thoroughly. A couple of those books I read many times, always the same few pages. I noted the Dewey Decimal numbers of those books and then went into the adult section, and there I looked through the books with similar Dewey Decimal numbers. The books in the adult section provided me with more details and with some vivid illustrations.

Another group of books that I remember checking out from the adult section was about boxing. I went into the adult section to look at books about sports and physical fitness, and I found several books about boxing techniques. I checked out these boxing books and took them home and practiced the techniques that the books illustrated.

One of these boxing books included instructions about how to make barbells out of a piece of pipe, a couple of tin cans and concrete. I followed those instructions and made a set of those barbells. I used these barbells to try to build muscles in my arms as I practiced my boxing techniques. The barbells looked like this:

The events I have described so far in this article happened before I began in seventh grade. In particular, I found the boxing books and built the barbells during the summer between my sixth grade and my seventh grade.

It was during that same summer that I acquired a lot of old magazines in the Concordia College library. I was in the library's adult section browsing around for books about some subject that interested me at that point. I don't remember whether I was looking for books about spies, about the Russian language, about sex, about boxing or some other subject. Anyway, while I was browsing through the shelves, I saw a college student, apparently working part-time in the library, who was taking a lot of old, bound volumes of magazines from some library shelves and loading them onto a cart. This college student was talking with someone else, and from that conversation I understood that he had been assigned to throw all these old, bound magazines away.

I asked the college student whether he really was throwing all these magazines away, and he replied that he indeed was doing so. I then asked whether I could have them all, and he said that indeed I could, because otherwise he intended to throw them into a dumpster. So, I took all the magazines from him and carried them home.

This was a lot of stuff, and I had to make many trips back and forth between the library and my home in order to move it all. I carried it all in my arms.

The magazines were all from the first half of the 1940s. The magazines included Life, Look, Saturday Evening Post and a couple other titles. Most of the magazines were bound by quarters. For example, all the Life magazines for the months January through March 1940 were bound in one volume, and all the Life magazines for the months April through June 1940 were bound in another volume, and sor forth. On that day I carried home a total of about 30 bound volumes of these old, various magazines from the early 1940s.

My Mom allowed me to keep all these bound magazines in our study in our home. I looked through those volumes many times, especially during the summer when I acquired them. This experience gave me a sense of what life was like when my parents were young. My mother was born in 1932, so during that period, 1940-45, she was ages eight to thirteen. I myself was eleven years old in the summer when I brought the magazines home from the library. Perhaps that is my Mom allowed me to keep them.

Those old magazines remained with our family as long as we lived in Seward, Nebraska. I think I had to get rid of them right before our family moved to Eugene, Oregon, but I don't remember whether I gave them to someone else or threw them into the garbage. It is possible that we did take them to Eugene, but much of our family's belongings burned up in a fire in a storage facility while we were waiting for our new home in Eugene to be built. If we did take them to Eugene, then they burned up in that fire.